Moving forward together

How to face brutal facts and prevail in the end

Dear Friends, In my post-election talk on “Moving Forward Together” with former Congressman Adam Kinzinger and his 1.3 million strong Country First community, I laid out a three-step process for facing brutal facts and prevailing in the end by: (1) recovering emotionally, so we can retrieve our better selves; (2) reflecting and resetting, so we can learn from what happened; (3) rebuilding on higher ground, so we can prevail in the end. In the next two posts, I expand on what I said there. This post focuses on the first two steps; the next on the third. I hope you take time to recover this weekend and begin to reset; we need each other. Ever grateful, Diana

The results of the November 5th election were and still are an agonizing gut punch for tens of millions of Americans. I know I feel it, and I’m sure many of you do too.

But it isn’t the first (and it won’t be the last) gut punch thrown by events that seem much larger than us. In 1940, the Blitz dealt the British people an almost fatal gut punch at the beginning of World War II when Britain was left to fight the Nazis alone. What Winston Churchill said then applies now: “If you’re going through hell, keep going.”

That’s what Vice Admiral James Stockdale did more than two decades later when he survived seven years of hell in the Hỏa Lò Prison in Vietnam. When asked how, he made a distinction between optimism and keeping faith. Those who clung to optimism would say, “We’re going to be out by Christmas” and then Christmas would come and Christmas would go, then Easter, then the Fourth of July, then Thanksgiving, then Christmas again. They died, Stockdale said, of a broken heart. From this, he learned:

“You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—

which you can never afford to lose—

with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality,

whatever they might be.”

Today you and I must face the brutal fact that almost one half of American voters cast their ballots for Donald Trump. At the same time, we must never lose faith that our democracy will prevail in the end.

How well we face one brutal fact will determine how well we face all the others, and it is this: Most people are not very good at facing brutal facts.

Too often, we look away or deny them altogether. We catastrophize, then self-medicate with food, alcohol, or drugs. We blame others without looking at ourselves. We downplay truths and obsess over uncertainties. We stoke false claims and we cling to false certainty.

Responses like these are natural reactions to deeply disturbing events. I’ve certainly indulged in one or more of them over the past few weeks, not to mention decades. But all they do is sap the energy and decimate the self-knowledge we need to prevail.

For democracy to survive, we the people will need to face some mighty distressing facts, so we can make something good out of them, a feat James Stockdale accomplished by never losing faith in the end of the story:

I never doubted not only that I would get out,

but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience

into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade.

My research on what millions of Americans are already doing to rebuild our democracy suggests that we can turn the brutal facts of the 2024 election into a defining event we would never, in retrospect, trade by taking three steps:

Step 1: Recovering emotionally, so we can retrieve our better selves

Step 2: Reflecting and resetting, so we can learn

Step 3: Rebuilding on higher ground, so we can prevail

In 2018, the people of Pittsburgh took these steps after the Tree of Life massacre. They grieved together; they reflected together; and they rebuilt on higher ground by remaking the space between the city’s historically segregated communities. This work, which they continued for years, made it possible for Pittsburghers to come to one another’s aid after the murder of George Floyd and the rise of anti-Asian hate during the COVID pandemic in 2020. Pittsburgh Journalist Tony Norman, who had a front row seat to each event and an historical understanding of their significance, later observed:

“The Tree of Life and George Floyd in a very horrific, ironic way made it possible for people to be vulnerable with each other. They forced people to cross bridges that they weren’t comfortable crossing. And once people got into the habit of crossing bridges, you began to see a new spirit emerge.”

After facing the brutal fact that their city was capable of such an unimaginable act of violence, people came together to grieve, to reflect and learn, and to rebuild their world.

This two-post series captures the hidden steps people took in the many stories like Pittsburgh recounted in Remaking the Space Between Us.

Step 1: Recovering and Retrieving

Over the past few weeks, what psychologists call our brain’s hot system has been working overtime in response to the emotionally flooding events related to the election. This part of our brain prompts us to:

• Think simplistically,

• React emotionally,

• Act impulsively, doing things we often regret.

Pushing aside feelings that trigger our hot system only intensify it, making us more reactive and less effective. So before doing anything else, we need to acknowledge the full range and depth of our feelings, get plenty of mental, emotional, and physical rest, and connect with family and friends for support. Once we’ve gotten rest and emotional support, it’s much easier to loosen our hot system’s vice grip, so we can shift to our brain’s cool system, helping us:

• Think more constructively and creatively about what’s happening,

• Consider complexities that might derail efforts later,

• Act strategically rather than reactively,

• Reflect on how we might be part of the problem rather than the solution.

To recover this weekend, I can’t think of a better film to watch with family or friends than Repairing Our World, documenting Pittsburgh’s response to the Tree of Life massacre. The film, produced by Not in Our Town, tells the story of how the people of Pittsburgh transformed trauma into strength.

Step 2. Reflecting and Resetting

We have much to learn from what’s happened, not just during the election, but in the years and decades leading up to it. To ensure we learn the right lessons, we need to resist the culturally ingrained and media reinforced Outrage Mindset which focuses on:

• Who’s to blame for our troubles, and how awful they are,

• How steep the climb ahead is, and how likely it is that we’ll fail or fall,

• Who is to blame if we do.

To prevail, we need to help one another shift to an Engage Mindset, which focuses on:

• Understanding what happened in a way that puts more (not less) power in our hands,

• Identifying the obstacles ahead and any toeholds we can use to climb over them,

• Figuring out how to make common cause with the people we need to prevail.

Simply learning about who voted for whom won’t help much, nor will learning what people’s binary, soundbite views are on immigration, inflation, or bathrooms, nor will convicting the usual suspects, even if they are “guilty” of contributing to results few will like once they materialize.

What will help is a far deeper, more granular understanding of the subtle and not-so-subtle demographic and ideological shifts at play—an understanding that can speak to the hearts and minds of people we have lost and whose trust we can and must earn back.

To come up with that kind of understanding, we need to move beyond outrage-fueled contempt to an engaged curiosity, so we can reconnect with and learn from the diverse range of people in the different groups that voted for Trump, and perhaps even more important, those folks so exhausted and despairing they didn’t vote at all.

When 13-year Marine veteran Lucas Kunce lost his recent campaign against Josh Hawley for Senate in Missouri, he emailed his supporters and posted the email on Substack. Instead of sending the typical post-election email that rants against the opposition and asks for money, Lucas simply thanked his supporters and then went on to say:

I’m working on a more in depth analysis of the campaign that we can all try to learn from (in the Marine Corps we call it an after action), but before that is done, I wanted to answer a question I have been getting from a lot of people who didn’t vote for Trump:

What were Trump voters like on the campaign trail?

Having been in every corner of the state and talked to thousands of people, I can confidently say it’s not the same with everyone.

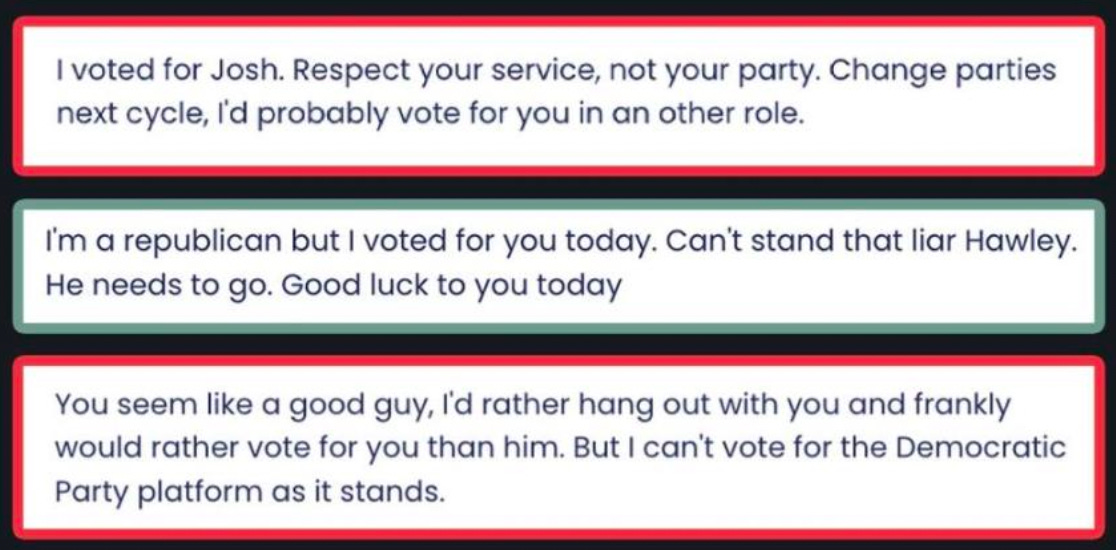

The remainder of the post captures what Trump supporters actually texted, emailed, or said, including this small sample I copied from the post:

He also included an almost verbatim account of his conversation with two Latino men waiting in line to vote at an early voting place:

The line to vote wrapped almost entirely around the mall. As I said hello to people I saw two Latino men around 30 years old quietly standing in line and not looking at me. I went up to say hi and they politely said hi back.

I told them who I was and that I wanted to meet people and ask for their consideration or see if they had any questions.

The older of the two, in pretty heavily accented English, said that he knew who I was, that he was sure I was a nice guy and that he liked me more than Hawley, but that there was no way he could vote for me. I asked him if there was anything I could do to change his mind.

He said he was sorry, but that he worked for a living and that Democrats had ruined the economy. That Trump was a businessman and therefore was the only one who could fix it, and that he just couldn’t vote for me because I was a Democrat and Trump was a Republican

This wasn’t the first time I had had a conversation like this with a Latino immigrant.

The takeaway from these, thousands more encounters along the campaign trail, and more of our campaign’s research is that many working people believe that they have found a political home — and it is not with the Democratic Party. It’s not clear that it’s with the Republican Party necessarily either, but more with Trump’s party — we’ll see if that impact sticks in future elections without Trump on the ballot.

An interesting thing that Trump has done in Missouri is that he brings out hundreds of thousands of infrequent Republican voters in the state who don’t necessarily vote otherwise — particularly in these last two presidential elections. Time will tell if this impact will continue without Trump.

The emails, texts, and conversations in Kunce’s post raise far more questions than they answer about how these folks came to hold the views they do. Odds are overwhelming that most of the answers we have to those questions will come from the same secondary sources these folks used to inform their views: social media, 24/7 cable news, politicians, pundits.

It is highly unlikely that they will come directly from the people who hold them. Our relationships within groups have grown so self-satisfying and those across groups so broken that it has become easier and easier to turn people who live and think differently than us into caricatures easy to hate and hard to like.

The brutal fact is this:

Too many of us have turned those who voted for Trump into a monolithic, undifferentiated mass from whom we keep our distance and express contempt.

If we do not change that—if we do not change our own hearts and minds—we will not stand a chance of changing anyone else’s.

That’s why I’m such a fan of Sarah Longwell’s Focus Group podcast. For years she has been talking with voters and getting inside their heads. Today her podcast with fellow podcaster Astead Herndon of the New York Times Run-Up Podcast launches an extended autopsy of the electoral results. As Sarah put it:

“We’re going to look at how we got here and give you an update at what the newly minted members of the Trump coalition have told us since the election about why they voted for him. But we’re not going to Monday morning quarterback every Harris campaign decision . . . [What] I want to talk about is why the voters found this campaign wanting. That’s the only way we are going to learn anything about this election.”

We could do the same. We ourselves could reflect with and learn from people whose views, beliefs, and experiences differ with our own. We could ask the kinds of questions Sarah asks and then listen to understand, not condemn, so we can find toeholds and build the relationships we need to move forward together. (For help in doing that, check out Amanda Ripley and Hélène Biandudi Hofer at Good Conflict, my friend Jeff Wetzler’s book Ask, and Remaking the Space Between Us for ideas and tools).

We have our work cut out for us. If we undertake it—after recovering emotionally so we can undertake it—we will build the insights and relationships we need to move forward together. If we turn away from that work, it’s hard to see how our democracy will prevail or our multigroup nation endure.

Stay tuned for the next post on how we can rebuild on higher ground, so we prevail in the end.

And please leave a comment below with any thoughts, questions, or suggestions this post sparked for you.