Rebuilding our democracy on firmer ground

That’s the long game. Here’s how to play it and win it.

Dear Friends, This post is part of a series based on a talk I gave to Adam Kinzinger’s Country First community following the November election. Now that our democracy is under ever increasing threat, resistance to Trump’s regime is on the rise while his popularity is fading. Resisting Trump’s regime is the inescapable short game we all have to play, and play hard, until we win it. While playing that game, however, we have to keep the long game in mind: how to rebuild our democracy on ground extremists can’t so easily divide and conquer. Only by winning that game can we stop repeating history. This post explores how to play and win the long game. Since there are no easy answers or quick fixes here, this post is longer than usual and may get cut off in your email (see “Tip” below). I am eager to learn what thoughts or suggestions the post sparks.

Tip: If the post gets cut off in your email, please click on "View entire message" and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Nine days after the January 6th assault on the Capitol in 2021, author Dan Simon published an article titled Who Voted for Hitler? Midway through the article, Simon notes:

We are respiring again across America after winning this presidential election and limiting Trump’s administration to one term. At the same time, nothing could be clearer than that we are not out of the woods yet.

Simon came to this conclusion after reading a 1982 book by historian Richard F. Hamilton, also titled Who Voted for Hitler? In the book, Hamilton drew on voting records in Germany’s municipal elections in 1928, 1930, 1932, and 1933 to meticulously trace how Hitler first gained, then consolidated power in much the same way Trump first gained, then consolidated power in the U.S. The book served as a warning — largely unheeded in the 40 years since Hamilton wrote these words:

Regrettably, one again sees the emergence of political gangsterism and the surfacing of totalitarian aspirations in many places throughout the world, this time, to be sure, with changed symbols, with different words and slogans, with a new face. It is as if human beings were condemned to experience such things as a phase in an ever-recurring cycle. There is a task for the genuinely critical intellectual—to break that cycle, to assure a more human course for human affairs.

That task has never been more urgent, and not just for the genuinely critical intellectual but for anyone seeking a more human course for human affairs. Ultimately, that task is up to us, and millions of Americans are already undertaking it.

But first things first. Before we can realize a more human course for human affairs, we need to better understand what leads so many people to cede their power to extremists and their so-called strongmen. Or put differently:

What keeps this ever-recurring cycle recycling?

Looking back on the rise of totalitarianism in the mid-twentieth century, Hannah Arendt offered a counterintuitive insight that often gets lost among her many others:

Totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia were not the problem.

They were the most horrific solution to a problem confronting all of humanity:

how to live in a pluralist world.

Humanity has yet to solve that problem, as the current rise in authoritarianism suggests. But what exactly is the problem pluralism presents, and how can we solve it without ceding our power to so-called strongmen?

To oversimplify what Remaking the Space Between Us explores in depth, the problem is this: In a democracy, people across different groups must arrive at solutions that work for most, if not all, of them, and they must do so in the face of forces that drive those groups apart. In the U.S., these forces include:

A history in which people were sorted into groups, then ranked along a hierarchy;

Win-lose, zero-sum cultural beliefs that pit these groups against one another, causing . . .

Widespread institutional breakdowns that have generated widespread mistrust;

Universal cognitive biases and emotional defenses that prevent We the People from seeing our role in perpetuating these forces rather than changing them.

Unaware of these forces and their power over us, We the People have succumbed to them, rendering us unable to work together to solve the problems most affecting our lives— problems like immigration, the price of food and gas, access to affordable health care, schools caught up in never-ending cultural wars, and so on.

As problems like these worsen and fester, people question the ability of democratically elected officials to solve the problems most affecting their lives and their communities.

Reflecting on how she won a congressional seat in a Trump district in Michigan, Democrat Kristen McDonald Rivet spent almost zero time talking about January 6th or the state of our democracy. That wasn’t because she doesn’t worry about it, but because she thought the best way to preserve it was through a concrete “agenda that makes it so everybody can thrive.”

Otherwise, over time — sometimes very little time — people turn to so-called “strongmen” or “men of action” to do what democratically elected officials seemingly can’t or won’t do: solve the problems that are preventing them and their families from thriving.

Trump is more popular with more demographic groups than liberals or progressives can comprehend, not so much because of policies like those outlined in Project 2025, but because he comes across as strong, straight-talking, and independent enough to cut through constant bickering and solve the problems eating away at us. Small wonder commentator Tucker Carlson imagines Trump as Daddy:

“Dad comes home and he’s pissed. He’s not vengeful, he loves his children. Disobedient as they may be, he loves them, because they’re his children. . . And when Dad gets home, you know what he says? You’ve been a bad girl. You’ve been a bad little girl and you’re getting a vigorous spanking right now. And no, it’s not going to hurt me more than it hurts you. No, it’s not. I’m not going to lie. It’s going to hurt you a lot more than it hurts me. And you earned this. You’re getting a vigorous spanking because you’ve been a bad girl, and it has to be this way.”

Those of us who worry about our democracy are so horrified by this metaphor it’s easy to overlook what it’s telling us that we need to hear:

As long as We the People are unable to work together, unable to solve problems

in our own communities, unable to resist divisive forces, unable to put the people’s house in order—we will make it harder for reasonable, democratically elected officials to survive and much easier for so-called strongmen

to persuade people to embrace them as Daddy.

Then, before you know it, more and more of us are traipsing further and further down a road toward an authoritarian future everyone abhors except those who hood-winked the rest of us into following them. If Ben Franklin were alive today, he would repeat what he said at the founding of our nation: “People who trade their freedom for temporary security deserve neither and will lose both.”

As early as 1814, John Adams very much feared that fate. “Oh! my soul!” he wrote in a letter to John Taylor, “I am weary of these dismal Contemplations! When will Mankind listen to reason, to nature or to Revelation? . . . Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide.”

Only by making plurality work for us can we break democracy’s repetitious descent into chaos and prove Adams wrong. Impossible? Well, it turns out that millions of people across the country are already doing just that.

How can we make plurality work for us, not against us?

After years studying how tyranny takes root, Hannah Arendt concluded: “terror can only rule over men who are isolated against each other . . . therefore, one of the primary concerns of all tyrannical government is to bring this isolation about.”

Those seeking to amass total power don’t have to work too hard to do that these days. Over the past five decades, threats posed by constant disruption and dislocation have driven We the People into increasingly insular, like-minded groups of the same ilk, while driving those groups so far apart that they fear and hate one another. It is hard to imagine a better recipe for producing the kind of toxic polarization that makes problem solving almost impossible in a democratic republic.

The way to combat this trend and break the cycle is hiding in plain sight.

In thousands of communities across America, millions of people have been working across lines of race, place, age, gender, and party to solve the problems extremists use to divide us. These citizens are working with one another in locally rooted, nationally connected groups to create common ground, so they can solve problems together. Musician Brian Eno captures the spirit of this movement in his forward to Jon Alexander’s 2022 book Citizens:

A different story is rising and ripening. It is a story of who we are as humans, what we are capable of, and how we might work together to reimagine and rebuild our world. This story does not show up on the media radar because that radar is resolutely pointed in the wrong direction. It’s expecting the future to be produced by governments and billionaires and celebrities, so its gaze is riveted on them. But behind their backs, the new story is coming together. It is slower, more diffuse, and more chaotic, because it is a story of widely distributed power, not of traditional power centres.

These citizens have already done the hard work of providing proof of concept for the rest of us. They have proved that We the People can in fact work together across divides to solve our most divisive problems. As documented in story after story in Remaking the Space Between Us, these groups are using people’s different backgrounds, interests, and perspective to create solutions no one group alone could imagine and all groups together can support.

Our job is to scale these efforts by building a more coordinated, mass movement on the infrastructure created by this loosely-coupled network of local groups.

The millions of citizens working across divides across our country have much to teach us about how to put plurality to work. Here are three lessons we most need to scale.

Lesson 1: Build relationships strong enough to solve divisive problems

The news and social media are awash with stories of tit-for-tat, retaliatory, zero-sum, one-upping, win-lose cross-group relationship patterns across demographic and ideological lines, whether those lines be Black/White, man/woman, young/old, poor/rich, rural/urban/suburban, straight/gay/queer, Republican/RINO/MAGA/Democrat. The list goes on and on, all of us either self-sorting or sorted into these socially constructed groups with which we come to identify and affiliate — all so we can create and perpetuate patterns that eventually kill us and/or our dreams for a better future. Sigh.

Our allegiance to one or more groups are set, as if in stone, by the world around us: both real and virtual. That world teaches us through patterned examples where we fit and how to face off against members of other groups, even in our own families and communities. How many of us go home at the holidays desperately hoping to avoid a ritual fight?

Despite the powerful role these patterns play, we rarely notice them. Like carbon monoxide, we ignore them until the damage they cause turns deadly.

In the shorter term, patterns like these give rise to what relationship expert John Gottman calls the Four Horsemen: criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. In the longer term, they produce a political culture so toxic and riven by high conflict that our democratic political system can no longer solve the problems chipping away at our lives and our democracy.

Small wonder so many voters want to “throw the bums out” or vote someone into office who will throw them out, even at the expense of our freedoms.

The single most important (and alterable) feature of these cyclical patterns is their self-reinforcing nature. Each side contributes to the pattern and makes it harder for the other side to respond differently.

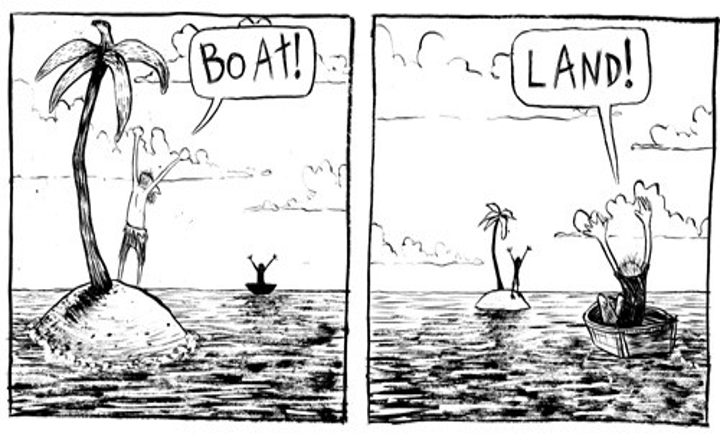

The cycle repeats — uninterrupted and potentially ad infinitum — for widely documented cognitive and emotional reasons: Each side only sees what the other side is doing, while remaining blind to what they are doing to perpetuate the pattern. It is this mutual blindness that locks these patterns into place, making them impervious to change.

Even worse, any effort to look at how both sides contribute to a destructive pattern today is criticized as “false equivalency,” as if the fact that one side’s actions are more egregious or harmful than another’s obviates the fact that the other side may be worsening their egregiousness—or at a minimum, acting in ways unable to reduce or disrupt it.

What Vaclav Havel said of systems you can say of these patterns: we are both their victims and their instruments.

Living in a media universe that converts toxic patterns into revenue streams, it’s easy to miss the countless examples of citizen groups across the U.S. and around the world who are disrupting these patterns and creating ones that put our differences to work to problem-solve, learn, and create. Skeptical? Check out these videos and see for yourself:

Video 1: Eleven Tennesseans, divided by their different political beliefs about guns, create a joint-proposal for curbing gun violence. See how they did it.

Video 2: Strangers meet for the first time and work together to solve a problem, unaware of the differences dividing them. See what happens when they find out.

Video 3: A Palestinian and Israeli, divided by a centuries-old cycle of violence resurrected by Hamas and Israel in October, explore how to break that cycle together. See how.

These videos are just the tip of the iceberg. In my research for Remaking the Space Between Us, I uncovered story after story of people from vastly different backgrounds and political beliefs coming together to solve problems affecting their lives and the lives of their neighbors.

The relationships these citizens built across divides were based, not on zero-sum, win-lose assumptions, but on mutual learning, mutual responsibility, mutual benefit, and mutual trust. If you look closely enough, you can discern the unspoken rules they used to build relationships that allowed them to define and solve some of our nation’s most divisive problems together:

Build a common pool of facts even if it takes time; it will teach you loads

(see Essay 17)Explore the different ways you see the same facts (Essays 11, 17, and 18)

Expand your views by actively seeking out new facts and perspectives

(Essays 12, 16, 18)Welcome and explore opinions different from your own (Essays 23 and 22)

Seek to problem-solve, not convince, cajole, or castigate (Essays 10, 16, 23, 24)

Ask genuine questions and respond authentically (Essay 18)

Be honest with yourself before trying to be honest with anyone else (Essay 17)

Bring curiosity rather than contempt to contentious issues (Preface, Essays 15, 16)

Learn from people with beliefs and experiences different from yours (Essays 12 - 18)

Search for common ground and create it when you can’t find it (Essays 18 and 24)

Be the helper others are looking for (see Essays 16, 18-22)

Help each other see what you can’t see on your own (Essay 17)

Invent creative, out-of-the-box solutions to “impossible” problems

(Essays 13 and 21)Ask for (and offer) help early and often (Essays 10 and 21)

Look at your role, not just others’, in creating polarized patterns (Essays 17 and 23)

Rules like these take into account the facts, beliefs, values, concerns, and needs people bring to the problems affecting their lives. As a result, they help people generate solutions they can live with because, even if not perfect, those solutions are much better than a status quo they can’t live with.

That may be as good as it gets in a pluralist democracy, which is pretty darn good when you consider where we are or might end up if we can’t make plurality work for us. Those who seek a perfect win at the expense of those who must lose destroy far more for everyone than they ever create for anyone. We’re better off building relationships that can put pluralism to work.

Lesson 2: Remake the space within and across groups

The disruption and dislocation of the past five decades have driven too many of us into insular, like-minded groups of the same ilk, while pushing those groups so far apart that we have become strangers to one another, to be feared, even hated. The space within most groups is now so closed and insular and the space across them so distant and hostile that we can’t get anything done together, threatening our democracy.

Paradoxically, many proponents of democracy have now formed their own closed-minded, insular groups, talking only with each other and pitting themselves against anyone who voted for Trump. Meanwhile, those who voted for Trump are pitting themselves against democracy proponents whose opposition to Trump strikes them as disconnected from their experience and irrelevant to their lives. Democracy expert Rachel Kleinfeld points out:

. . . those who voted for [Trump] are not going to be shocked by Trump’s personality, vindictiveness, or the policies he is pursuing. He has dominated politics in America for nearly a decade. . . the appeal of personal strength, crushing opponents, delivering on promises, and helping the majority over “special interests” are long-standing political winners. Fighting Trump for what he is is likely to fail.

To wrest control of our democracy from extremists, we need enough Trump voters and enough nonpartisan, disengaged, and disaffected voters to move away from Trump and towards an alternative they can support. As Kleinfeld argues:

. . . Pro-democracy forces should wait for moments of excess that make large groups of Americans, including Trump’s supporters, squeamish, and they should drive these moments home, hard and with repetition over time… a major communications operation should seize on the kinds of issues that have an emotional punch or trigger a strong disgust reaction.

That operation, according to Kleinfeld, should target those who are less partisan or politically engaged and include that “ancient form of information transfer: conversations between people who know each other:”

Americans who are separated are more likely to think the worst of one another, but democracy is built on positive, engaging forms of community at the local level, including friend and family networks that cross partisan boundaries. If those formal and informal relationships are infused with messages that spread hope, joy, and connection, they create a medium through which new messages and “vibes” can pass.

It can be terrifically hard to move out of the comfort zone of our own groups and mingle with those whose views and beliefs are different from or even opposed to our own. That’s why it helps to join community groups focused less on whether Trump is good or evil and more on, say, fixing the damn roads, as Michigan’s Governor Whitmer put it, or curbing gun violence, or rebuilding a community after a flood or fire, or supporting the local schools.

These are the problems Americans care about. By working on them together, we not only remake the space between us, we offer an alternative to the darkness of division. To learn more, go to www.remakingthespace.org/learn-act and www.remakingthespace.org/stories.

Lesson 3: Build a citizenry of friends worthy of democracy

The vast majority of elected officials today must play to their base to win elections. Yet, once elected, playing to their base prevents them from getting anything done. To get out of this Catch-22, elected officials need We the People as much as We the People need them.

This way of thinking — that We the People have an important role to play and are responsible for playing it — doesn’t come naturally. While We the People are guaranteed innumerable rights by the U.S. Constitution, we are expected to do only four things: obey the law, pay taxes, serve on juries, and register with the Selective Service. Beyond that, our responsibilities are pretty much up to us, including whether to stay informed or to vote. Nowhere in formal documents or informal custom are we expected to do much, if anything, else.

Fast-forward 234 years since our founders ratified the Bill of Rights, and We the People are no longer the solution our founders imagined but the problem they feared.

As Bulwark editor Jonathan V. Last pointed out in his May 2023 post “The People Are the Problem,” many of our current political woes spring not only from big-money donors but from small-dollar donors fueling the ascendancy of candidates that range anywhere from poor to downright dangerous—Trump only being the most recent and egregious example.

But here’s the rub, as Last points out: “You cannot expect normal people to have considered opinions about complex issues such as the debt ceiling or immigration policy, or the war in Ukraine. Normal people have lives; they don’t read a lot of news. It’s not fair to expect them to be well informed.”

Fair enough. Yet perhaps it is expecting so little of so many for so long that has brought us to where we are today. Social science research shows that you pretty much get from people what you expect of them, with higher expectations leading to higher performance and lower expectations leading to lower performance.

Since our democratic system depends so much on We the People, perhaps it’s time we expect ourselves, not to do more, but to do better. Or as Last says, “Good luck, America.”

Asking people to “do better” raises two very tricky questions:

How can we avoid the possibility that “doing better” just leads people to fight even more vigorously or violently for their side to win and the other to lose? Heaven forbid!

And how can “doing better” be something most people want to do and be able to do, not just feel obliged to do, then fail to do?

The short answer? By reimagining our role as citizens, something many of us are already doing and scholars have explored for decades, which leads to a longer answer.

In 1980, long before today’s democratic crisis, award-winning political scientist Jane Mansbridge anticipated it in Beyond Adversary Democracy. The book’s close study of two very different communities showed how an adversarial conception of democracy, untempered by a more cooperative, consensus-oriented attitude, elevates conflicting interests above shared interests, turning citizens into adversaries.

Later on, in Talking with Strangers, political philosopher Danielle Allen explored what would happen if citizens in a democracy viewed each other, not as adversaries, but as friends?

Friends know that if we always act according to our interests in an unrestrained fashion, our friendships will not last very long. Friendship teaches us when and where to moderate our interests for our own sake. In short, friendship solves the problem of rivalrous self-interest by converting it into equitable self-interest . . . Whereas rivalrous self-interest is a commitment to one’s own interests without regard to how they affect others, equitable self-interest treats the good of others as part of one’s own interests [my emphasis].

When it comes to a pluralist, multigroup democracy like ours, citizens-as-friends has an unparalleled competitive advantage over citizens-as-adversaries.

Instead of creating patterns of domination and acquiescence in the face of loss and conflict, citizens would create patterns of reciprocity and mutuality, especially when it comes to our rights and responsibilities in relation to one another. We would see that even if we have the right to do something, it may not be the right or responsible thing to do with a friend upon whom we depend to do the right and responsible thing with us. Instead of exhausting the trust and goodwill we need to make our pluralist endeavor a success, cross-group friendships would revive both. Seeing ourselves as friends, we would act like friends, making sure that no one group bears the brunt of society’s losses over time.

The millions of citizens solving problems in communities across our nation are solving those problems because they are working together as friends, not adversaries.

The work they’re doing — in whatever time they have to do it — does not feel burdensome to them. It brings them meaning, learning, fun, camaraderie, community, pride, and purpose. To name only a few of the successes owed to these friendships:

White and Black, old and new residents in a predominantly white city in a predominantly white state showed how immigration could revitalize a city’s dying economy.

A group of gun rights activists and gun control activists came together after a school shooting to learn about their different experiences of guns and to draft a mutually agreed-upon proposal for reasonable gun control to present to the state legislature.

After a mass murder at a synagogue, people from across an historically segregated city built cross-group relationships strong enough to heal their city and reduce hate.

Tens of thousands of people across demographic and ideological divides are coming together to learn from and with one another about our toughest probelms in webinars, virtual book clubs, online support.

Citizens in a western city showed up for neighbors targeted by hate crimes, then launched a national movement to fight hate and foster connection.

An alliance of faith leaders and parents in a midwestern city joined together to put a stop to the culture wars harming their kids’ education.

A group of journalists built an organization to reinvent journalism by reporting on what people are doing to solve problems not just create them. They’ve now trained tens of thousands of journalists and published thousands of stories.

Hundreds of thousands of citizens in an organization founded by former Representative Adam Kinzinger have come together to connect and to take collective action every week to protect our democracy.

These citizens have already created the infrastructure upon which we can build a movement made up of coalitions broad enough to wrest our democracy back from extremists and rebuild it on ground they can’t so easily divide and conquer.

What will it take to succeed?

In his February 21 post on Substack, political analyst and commentator Robert Reich reminded us of a basic truth about change in a democracy that we sometimes forget:

. . . the Democracy Movement now emerging will require at least a decade, if not a generation, to rebuild and strengthen what has been destroyed, and to fix the raging inequalities, injustices, and corruption that led so many to vote for Trump for a second time.

Those of you who want the leaders of the Democratic Party to step up and be heard are right, of course. But political parties do not lead. The anti-war movement and the Civil Rights Movement didn’t depend on the Democratic Party for their successes. They depended on a mass mobilization of all of us who accepted the responsibilities of being American [my emphasis].

We will prevail because we are relearning the basic truth — that we are the leaders we’ve been waiting for.

James Baldwin once said that changing the world doesn’t take numbers, it takes passion. He is undoubtedly right, and yet numbers do help.

But just how many numbers do we actually need?

According to Erica Chenoweth’s longitudinal research on political change, you need only 3.5% of a nation’s population for a nonviolent movement to succeed at creating significant change. In America that means we need only 11,725,000 people to reclaim our democracy from extremists and rebuild it on firmer ground. Given that 77,301,997 people voted for Harris and untold millions are propelling the citizen movement already afoot, we’re well on our way.

“We’ve never fully lived up to the idea of America,” Joe Biden said at Jimmy Carter’s funeral. “But we’ve never walked away from it either.”

Let’s not walk away now. Join us in whatever way fills your cup, and stick with it no matter how many times we get knocked down. That’s how we keep moving forward. That’s how we win.

Thank you for highlighting the challenge and the opportunity in any given moment (even when it's hard to see). This piece is such a beautiful testament to the power of relationships (within and across groups)—not just as a nice-to-have, but as the very foundation for meaningful change.

Thank you for another thought provoking and inspiring piece of writing, Diana! It leaves me curious about what you and others think about a coordinated effort to distill lessons and harness the collective power of the citizen-led efforts to solve problems and embody the leadership we are waiting for - how might we actually do this? Anyone want to get together and brainstorm? I’m in!