We are the ones we’ve been waiting for

We have much to learn from those closest to the problems we all want to solve

This post is inspired by my interview with Jesús Gerena, the CEO of UpTogether. a systems-change organization disrupting mainstream approaches to poverty after decades of failure. Click here to see the interview transcript.

In May 2022, the city of Austin, Texas launched a publicly funded guaranteed-income pilot program to invest $1.1 million directly in communities, the first of its kind in the state. In its first year, the pilot invested in 135 low-income families experiencing housing instability. Every one of those households used the unrestricted money they received to cover basic needs like housing, food, and utilities, while 59% used a portion of the funds to support other community members in need. After a year, the percentage of members receiving government housing assistance was down by half.

The benefits of the pilot extended beyond economic indicators. Parents were able to be more active in their children’s lives. People reported feeling a deeper sense of connection to their neighbors. Mental health improved. The modest cash investment empowered not just individuals but communities to work together to meet their own needs in ways that benefited everyone, not just some.

The Austin Guaranteed Income pilot was inspired and shaped by the work of UpTogether, a systems change organization working to end poverty, in part, through unrestricted cash investments in low-income families and individuals. UpTogether’s work is rooted in the belief that the people closest to the problem of poverty can best figure out how to get out and stay out. That belief empowers communities to work together to build a better future for everyone. When I interviewed UpTogether CEO Jesús Gerena last week, he put it this way: “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.”1

Believing is seeing

According to the US Census Bureau’s statistics, 37.9 million Americans were living in poverty in 2022. That means 11.5 percent—more than one out of every ten of us—were (and still are) living a life of poverty. That percentage has not changed much over time. Since 1973, with only three exceptions when the poverty rate rose to 15 percent in 1983, 1993 and 2011, the rate has pretty much stayed just below or above 11 percent. 2

That is not for lack of trying. Many a politician and policy-maker has broken his or her axe trying to cut the poverty rate—President Johnson’s War on Poverty the most notable. The reason for this repetitious failure may be simpler than such a complex, stubborn problem might suggest.

Those like Jesús, who are intimately acquainted with poverty’s causes and effects, think the most powerful reason lies in two widely shared but unexamined beliefs.

The first is that those living in low-income communities lack the ability to make good choices about how to spend money or live their lives. According to this belief, any money low-income people get from the government will only be spent on fancy cars, big TVs, or drugs. Therefore, policies should be designed to tightly control when and how much aid low-income people get for what. What’s more, aid should be shut off as soon as the policy dictates a person or family no longer needs it.

Jesús and those at UpTogether hold a different belief. Though well aware that some folks in low-income communities spend money on fancy cars, big TVs, or drugs, they also know that the same can be said for those living in all other communities. Most people living in poverty are working hard to get out. Since they are closest to the barriers they face, UpTogether believes they will know best how to allocate resources to get over those barriers. In their view, then, policies like guaranteed income have the best chance of accelerating families’ initiatives.

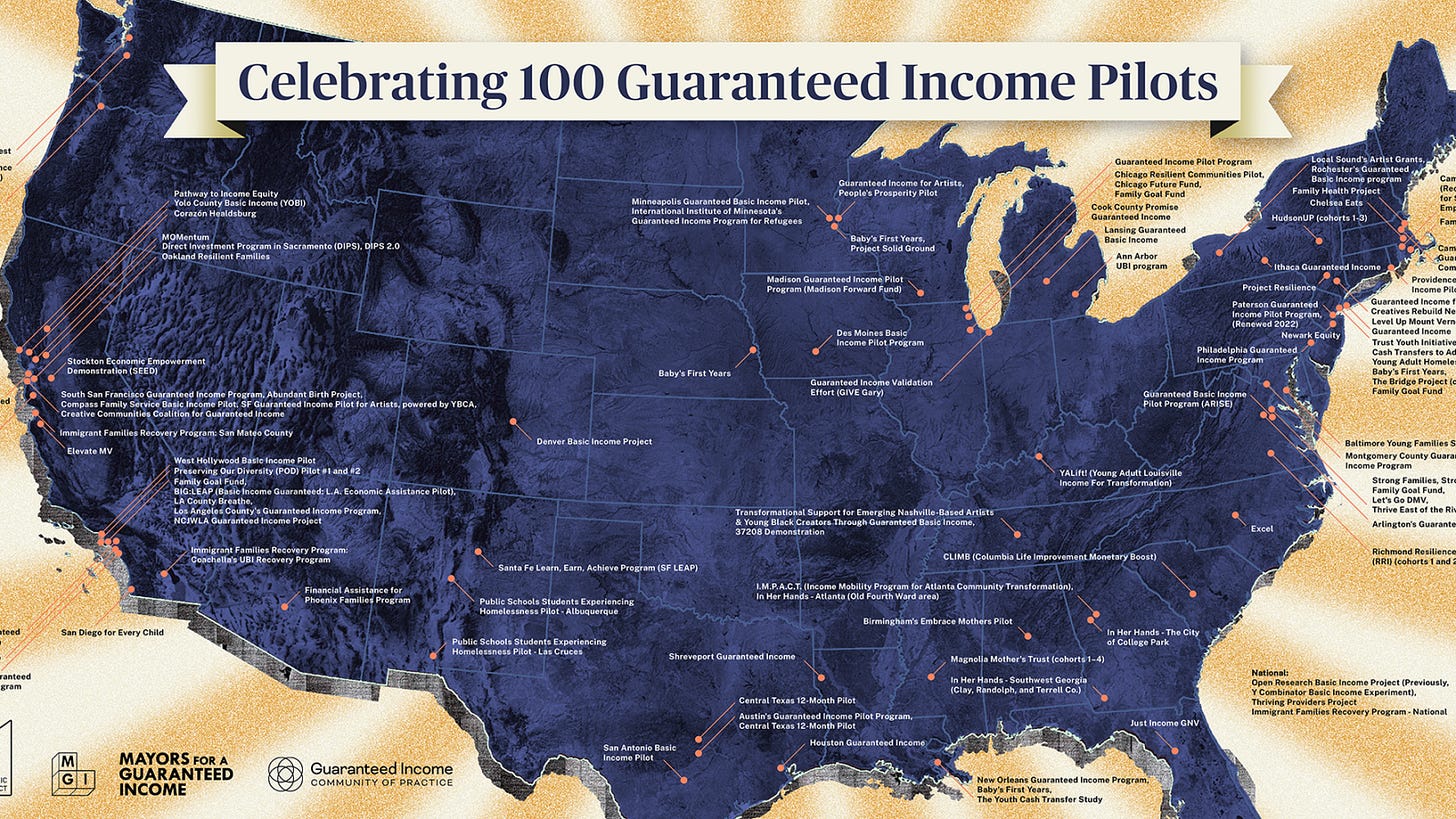

When you put these competing beliefs toe to toe, the people-know-best belief wins hands down. In the past few years, that belief has generated over 100 pilot programs, all of which have shown excellent outcomes for children and impressive gains in parenting, adult mental and physical heath, food security and housing stability.3 Meanwhile, the poor-people-can’t-be-trusted belief has repeatedly produced failed policies and programs—in large part because it is tethered to a second, companion belief. . .

This second belief holds that poor people should not live off of the largesse of government, because it only encourages dependence, and it is unfair to those who work hard for their money. This belief has long proliferated policies that cut off monies to families as soon as they rise above the poverty line, leading most families who have worked their way out of poverty to fall back down as soon as a crisis hits.

Jesús and those at UpTogether see this cycling in and out of poverty as one of poverty’s hallmarks, a hallmark that mounting evidence suggests is driven by poor policy, not poor people.

This past year, Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond has turned this second belief on its head.4 In his bestselling book Poverty by America, Desmond documents how those families who need the government’s help the least benefit the most from its policies.5

In a Forbes article on Desmond’s book, Erik Sherman cites a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) study from 2015 that showed about $195 billion of the $270 billion the federal government spent on housing was in the form of tax code-based deductions which, as Sherman documents, disproportionately benefit the wealthiest. The remaining $75 billion, or less than a third as much, is spent on the poor. Sherman goes on to cite another of NBER study from 2021 estimating that 36 percent of unpaid federal income taxes are owed by the top 1 percent and that collecting those unpaid taxes would increase federal revenues by about $175 billion annually. Sherman adds: “That would pay for the child tax credit and still leave $50 billion additional to put toward the national debt. But who’s taxes get the most scrutiny? People who earn very little.”6

If we are genuinely worried that governmental benefits breed dependence and are inherently unfair, then perhaps it is time to scrutinize all governmental benefits, looking at all those who receives them in one form or another and for one reason or another. Short of that, we will continue to impose a burden of proof on one group (the poor) that we do not impose another group (the rich), undermining trust in the fairness of our systems.

A controversial notion, I know. I saw what happened when Jesús once mentioned to a group of wealthy donors that the wealthy also received governmental benefits. One of them took great offense and cautioned Jesús not to get political. That donor is far from alone. Many of those with great wealth either believe they have earned governmental benefits and that their wealth is evidence of that—or they simply don’t think about tax breaks as benefits. Either way, most would say it makes sense to design tax law to incent the wealthy to keep doing the things that made them, well, wealthy. And even though data now show that their wealth doesn’t trickle down, as argued for so long, they might still argue that it is only fair to reward good performance.

Fair enough. But why wouldn’t that same logic apply to low-income families? Right now, those who make it out of poverty lose benefits and often fall back into poverty. Cutting off benefits punishes rather than rewards or supports their accomplishments. It makes little sense either for these families or for our society. It is far more likely to reinstate dependence than to cement independence.

Seeing is believing

Those who make it out of poverty know this firsthand. They know what it takes to move out of poverty and once out, to stay out. Perhaps we should listen more to their stories and see what they see, so we can shift erroneous beliefs about the trustworthiness and dependence of low-income people and their families.

UpTogether has spent decades generating the firsthand stats and stories we need to shift our beliefs. Founded in 2001 as the Family Independence Initiative, UpTogether embodies the essence of American democracy. Working with few staff and a lot of conviction, they sparked a movement of low-income people working together to build a better future for themselves and one another. It is a movement of the people, for the people, and by the people, amplified by UpTogether’s belief in the power of community, choice, and capital to support but never determine the direction of their efforts.

When Beatriz first joined UpTogether in 2010, she was the mother of two young sons, working multiple jobs to support her family—cooking, cleaning, and doing childcare. With every waking hour devoted to her work or her children, she had little time to create the kind of close relationships she wanted. A community-builder by nature, she did her best to form connections with other immigrant mothers in East Boston, but everyone was just as exhausted and financially strained as she was.

When Beatriz learned about UpTogether from Jesús, she saw an opportunity to uplift not just herself but other mothers in her network. So the first thing she did was gather a group of women together in her living room for mutual support. Aptly calling themselves the Pioneras, this group of women went on to pioneer ways to use the unrestricted money from UpTogether to create a collective “kid’s fund,” providing cultural and educational activities for the community’s children.

At the same time, Beatriz used UpTogether’s investment in her to buy industrial food equipment so she could start her own catering company. To manage the business, she joined programs teaching financial literacy, always sharing what she learned with others in her community. And to juggle childcare responsibilities with the demands of a growing business, she bought her first car. With only a modest investment from UpTogether, Beatriz was able to create a pathway out of poverty while helping others do the same.

Over a decade after that initial investment, Beatriz continues to thrive. She now owns a cleaning company in addition to her catering business. She continues to serve her community, connecting others to the resources they need to support their children, grow their businesses, and expand their knowledge. But most exciting and gratifying for her, her two sons won full scholarships to Roxbury Latin, a prestigious private school, and more recently, full scholarships to Tufts University.

Reflecting back on her journey, Beatriz recounts how her life changed through her involvement with UpTogether. “I now had the power to not only help myself and my family, but to help other people in my neighborhood. More and more people like me were arriving in East Boston and it felt good to offer them knowledge. It made me feel alive.”

Abolishing Poverty

If seeing were believing and not the other way around, we would be much further down the road to ending poverty. The results of 100 guaranteed income experiments, described in this video, show that when you believe in and invest in people, they thrive.7

And, if seeing were believing and not the other way around, elected officials in ten states would not be seeking to prohibit them. Yet they are.

Despite the positive results generated by 100 pilots, policymakers in 10 states have prohibited or are seeking to prohibit tests of guaranteed income that use public funds.” According to Mary Bogle of the Urban Institute, they are claiming that they are “socialist” – despite having produced better results than existing governmental programs and despite their embodying core American values like liberty and efficiency. “In fact,” says Bogle, “these deeply American characteristics may explain why outcomes for recipients are often so positive.”8

If we are ever going to win the war on poverty, we will need to reduce the distance between socioeconomic groups, so we can see the people and families living in poverty for who they really are, not the distorted, attention-grabbing images TV curates for our entertainment.

UpTogether closes the distance between us by collecting and amplifying stories and statistics on the lived experiences of people lifting themselves out of poverty. Those lived experiences, captured over time, prove what Jesús says: "We are the ones we've been waiting for."

If there is a moral imperative for our age equivalent to that of slavery, it is poverty. Matthew Desmond hopes more and more of us will become “poverty abolitionists”— that we imagine a “politics of collective belonging,” so we can usher in an age of shared prosperity and true freedom.

To see the statistics and stories UpTogether has gathered, please go to UpTogether.org.

Notes:

I was a board member of the Family Independence Initiative from 2011-2018

Bill Fay, “Poverty in the United States,” debt.org, December 21, 2023.

See data from the Economic Security Project. https://economicsecurityproject.org/work/guaranteed-income/

Matthew Desmond, Poverty by America. Crown, March 2023. Kindle Edition.

Erik Sherman, “How Government Aid Focuses On The Wealthy First, The Poor Last” in Forbes, March 26, 2023.

Ibid.

See data from the Economic Security Project. https://economicsecurityproject.org/work/guaranteed-income/

See Mary Bogle, “Banning Guaranteed Income Programs Undermines American Values.” The Urban Institute, April 24, 2024 https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/banning-guaranteed-income-programs-undermines-american-values.